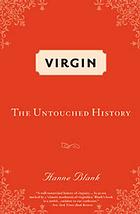

I love the things I can pick up and read in the name of thesis research. Take, for example, Elizabeth Fraterrigo’s Playboy and the Making of the Good Life in Modern America (New York: Oxford U.P., 2009). I saw the book by chance on the shelf at Borders a few weeks ago and while I would have read it eventually anyway (what’s not to like? sex! gender! money! drama!), I realized after pondering for a day or two that I could consider it background research on American postwar culture. So off to the library I trundled. (Or rather, off to the online catalog I clicked, forthwith to inter-library loan a copy through the Brookline Public Library).

I love the things I can pick up and read in the name of thesis research. Take, for example, Elizabeth Fraterrigo’s Playboy and the Making of the Good Life in Modern America (New York: Oxford U.P., 2009). I saw the book by chance on the shelf at Borders a few weeks ago and while I would have read it eventually anyway (what’s not to like? sex! gender! money! drama!), I realized after pondering for a day or two that I could consider it background research on American postwar culture. So off to the library I trundled. (Or rather, off to the online catalog I clicked, forthwith to inter-library loan a copy through the Brookline Public Library).

And Ms. Fraterrigo did not disappoint. This dissertation-turned-book is a richly researched yet highly readable account of Hugh Hefner’s self-re-invention as the playboy of his dreams, a life he carved out for himself with relentless hard work and not a little luck after the dissolution of his youthful marriage and a series of unsatisfying desk jobs. Hefner, Fraterrigo convincingly argues, took various cultural elements in already in play (dissatisfaction with suburbia, anxiety about masculinity and women’s increased visibility in previously male spaces, a rise in consumer spending, postwar debates about what constituted the “good life,” and the scientific examination of human sexuality) and packaged them in a highly-successful formula that catapulted him to the top of a cultural and financial empire.

She draws two fascinating (if superficially unlikely) comparisons between Hefner and women writers of his day. First, she suggests a commonality in thought between Hefner and early feminist rhetorician Betty Friedan (author of The Feminine Mystique). Both Friedan and Hefner drew on their own personal experience to build a critique of the hegemonic postwar culture and its emphasis on the middle class, suburban nuclear family. In response to an unsatisfying homelife, both championed participation in the capitalist economy (as both worker and consumer) as a potential route to self-realization (see pp. 26-36).

Second, Fraterrigo points out the striking parallels between the ideal woman as articulated by Hefner in the page of Playboy (and in real life by the women who worked as Bunnies in the Playboy clubs) and Helen Gurley Brown’s “Single Girl,” found in the pages of Sex and the Single Girl first published in 1962. Both Hefner and Brown managed to carve out a place for singledom and pre-marital sex in culture dominated by the value of marriage and family. Yet they did so in ways that in no way challenged the status quo of inequitable gender relations or the notion of gender complimentarity (the idea that men and women “naturally” perform different, though complimentary, roles in society).

Brown’s Single Girl fit easily into the harmonious system of gender roles supported by Hefner. She made few demands on the male pocketbook [unlike a wife], aside from accepting the occasional gift or evening on the town, and instead made her own way as a working girl. Like the playboy, she strove to work hard and play hard too; yet she had no pretensions about achieving much power or earning vast sums of money through her role in the workplace. Instead, she accepted her marginal economic position and limited job prospects with a smile on her well-made-up face. Though she may not have enjoyed the same degree of autonomy and plentitude as the playboy, the Single Girl shared his sensibilities . . . [she] was both a handmaiden in the liberalization of sexual attitudes in the 1960s and the ascent of a consumer-oriented singles culture (132-33).

As the Swinging Sixties gave way to the cultural and counter-cultural revolutions of the early 1970s, Hefner found his idealized Playboy — once a symbol of avant garde youthful revolt against the status quo — derided by both men and women of the Movement cultures who critiqued his unabashed materialism and stubborn support of strictly segregated gender roles. He was taken aback by the “aggressive chicks” of the women’s liberation movement who pointed out that structural inequalities and oppositional gender typing (the strict separation of “masculine” and “feminine”) left women in a systematic disadvantage. Despite Hefner’s (and Playboy‘s) support of such feminist causes as women’s right to sexual expression, sex outside of marriage, access to abortion, and women’s participation in the workforce, he seems — according to Fraterrigo at least — to have balked at re-imagining a world in which the division of gender roles was less strictly dictated than it had been in the decades of his youth.

In this, Hefner is far from alone to judge by the continued popularity of “complementarian” arguments for “traditional” feminine and masculine roles among various conservative groups and even in some feminist circles — yet I am perennially puzzled by the amount of fear and resistance appeals to loosen gender-based expectations routinely encounter. While beyond the scope of Fraterrigo’s deftly-woven narrative about Playboy and the postwar culture of freewheeling consumerism it helped to legitimate, it is certainly a question which Playboy encourages us to ask: What, exactly, is at stake for individuals who defend complementary gender roles? The women’s liberationists of the 1970s thought they had the answer: unfettered male access to women’s bodies and the uncomplaining domestic support of housewives and secretaries. Fraterrigo’s tale, however, suggests that the answer is — while still containing those elements — far more complex (and more interesting!) than it appears at first glance.