A lightly edited Twitter thread I wrote today prompted by this Tweet that crossed my timeline:

I mostly don’t read or talk about student loans and the PSLF program because it’s a shortcut to panicked paralysis but today let me share my story about debt, grad school, and public service.

My family circumstances made it possible for me to graduate with my B.A. only $5k in debt. I went to a school where my father worked on staff, so I got tuition remission and I lived at home to keep expenses down. So I began the grad school search and application process not very deep in a hole. Between graduating college (May 2005) and beginning grad school (August 2007) I worked at part-time jobs that paid hourly wages of between $7.50-$10.00/hour. I had been working part-time for a decade or more at that point and in that context a $10.00 wage seemed grand! One of my jobs even gave me the option to open a 401(k) to which I began to slowly contribute. I had low expenses because I didn’t have kids, wasn’t maintaining a house or a car, and I was able to live with my parents. I started paying down that $5k of student debt. I put some savings away for a computer to get me through grad school and a cushion to get me through a cross-country move. I was able to arrange a transfer with one of my part-time jobs (Barnes & Noble) from West Michigan to Boston so that I arrived with a job waiting (even if it only paid $9/hour). Most people don’t have the family support and resources to do this kind of planning when they’re making below living wage.

I was warned by faculty mentors and career services people at my undergrad, when applying for grad school, that student loans were likely inevitable. I was looking at M.A./M.L.S. programs and was told the funding goes primarily to PhD students. I didn’t want to enter a PhD program. But I did need an advanced degree if I wanted to pursue work in the library science field, and I wanted to continue my history scholarship as well both because I loved historical research and writing and also because it would help me on the job market. I chose a private school (Simmons College, now Simmons University) for my grad program for personal and pedagogical rather financial reasons. I wanted to get out of Michigan for a while, and the program offered an integrated archives-history track with small cohorts that sounded like a good fit.

In retrospect I didn’t have much experience cost comparing. I had never shopped for an undergrad college — I had gone where tuition was free, because that seemed like an offer I’d be foolish to refuse. So I was naive. But I had also grown up in a context that predisposed me to pick based on the program first, and cost second. I had been encouraged by all of the adults in my life to evaluate learning experiences first on the basis of whether they supported the personal goal of making a meaningful life and contributing to the collective good and then, second — after deciding whether the learning on offer was a good match — think about whether it was practically feasible. I actually still believe that is a valuable approach. But it is an approach that exists uncomfortably alongside the skyrocketing expense of higher education. “Is this practically feasible?” is a different starting place from, “What is the smartest financial decision?”

When I got the financial aid package there was some merit based scholarship money … and a projected ~$60k in student loans for the four years of the program. Scary numbers I had no basis for evaluating. (Another reminder that I was a white, middle class young adult who was a third generation college graduate with PhDs in my extended family. Many people go through this with way less cultural competency in the higher education marketplace. And I was still struggling to interpret my options.) So. I get the aid package and am at sea trying to evaluate it. My father has a colleague who does financial advising and he offers to go over the numbers with me for free (again, something most people do not have in their lives). I put together a spreadsheet of projected income and expenses. The financial advisor is impressed I can spreadsheet! He looks over my numbers and the takeaways from our conversation are these:

- Educational debt is an investment. While I’m not being encouraged to sign for loans willy-nilly, the loans on offer are all government loans with non-predatory interest rates and flexible options for repayment based on circumstances. Taking out loans to pursue professional training is not considered a poor financial strategy.

- The first year of grad school will likely be most expensive, as I transition to a new city, look for work, look for an apartment, find roommates to cost-share with, etc. I can borrow a bit more in year one and likely bring borrowing down in subsequent years as my expenses go down and my earning goes up.

- The best practice was not to take out more in loans than I could expect to earn as an annual salary once I had completed my degree. If I kept that equation in mind, it would help keep my monthly payments after graduation to something my earning power could realistically absorb.

I took his advice, bit the bullet, and decided to accept the offer of admittance. It was scary, but I felt I had done my due diligence and no one had raised red flags so I pressed forward. And his advice, as far as it went, was pretty decent. I’m glad I stuck to federal loans, and during graduate school I was able to reduce the amount I accepted in loans each year. I worked multiple jobs (that paid $12 and even $14/hour!), accepted stipended teaching and research assistantships, and shared a 500sqft apartment and living expenses with another graduate student (reader, I married her). Living in Boston is fucking expensive. In my hometown, the apartment that I had shared with a roommate in college cost $500/month. We each paid $250. I knew Boston would be expensive but there’s a difference between knowing on paper a major metropolitan area is more expensive than your hometown and writing a rent check for $1250 every month (today that rent check is $1900). But Boston was where my graduate program was, and it is/was where my job (and my wife’s job) opportunities were — and still are. There was no way, during graduate school, we could pay living expenses working jobs that paid $12-$14/hour, even with both of us working. So loans were a necessity part of making ends meet while we were balancing school, work, and life.

As I have written about before, the reality of taking on so much debt — I had never even had to pay interest on my credit card balance, which I paid in full every month! — was physically toxic to my system. I was so frightened of, and humiliated by, the fact of having student loan debt I woke up nauseated every day for the better part of that first year. I felt like I should have been clever enough to find a different way. It felt like irresponsibility to incur debt at all.

While I was in graduate school, the 2008 financial crash happened. NO ONE was hiring. We all felt lucky not to be let go (if we weren’t let go). It was around this time that one of my colleagues made me aware of the Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF) program. This was before anyone, anywhere had been making payments for the necessary ten years to apply for forgiveness. The criteria seemed opaque but we puzzled through the fine print and concluded our non-profit cultural institution was likely a qualifying employer. THANK GOD there might be light at the end of the tunnel. A safety net by which the chronically low-paying jobs in our field (libraries, archives, and museums) were recognized as a public good and the financial burden we were all carrying in order to do that service work might be lifted.

Notice I say “might.” We were all wary of the PSLF program because it seemed too public-spirited to be true in the age of government austerity. It was way too uncertain a possiblity, way too far in the future, to make any major decision life based upon a “might.” Certainly not as we were watching colleagues be let go, watching the job ads slow to a trickle, watching the housing crisis unfold nationwide.

Just as I was going on the full-time, post-grad school job market in earnest, I was offered a promotion to full-time at my current workplace. The starting salary was $34k/year. So while my student loans (approaching $60k by graduation) met the guideline for not exceeding the “typical” Boston salary in the library sector ($62k) the job — full time! with benefits! in a shitty economy! — on offer was only half that. So the realities of the situation were this: I could accept a full-time job with colleagues I felt good working with, doing work I felt good about, in a shitty job market and enroll in an income-based student loan repayment plan OR I could keep looking for a job, perhaps even in other sectors I wasn’t trained for, that would allow me to pay off my student loans in the “standard” ten years. Don’t forget that I had/have a partner who also has student loan debt we are jointly responsible for, who was simultaneously making these same calculations around accepting contingent, part-time work or … remaining on the brutal job market.

Remember that my wife and I both work in an entire industry — non-profit, cultural heritage work — where staff are chronically underpaid, especially in relation to our training and the financial investment they were encouraged to put into that education, and all told (and tell eachother) we should be grateful for work we love. Are we foolish to accept and repeat this story? Maybe. But the story is told around us and dictates the conditions of our work in material ways not entirely in our individual control. When an entire sector is organized around the economy of workers expected to be grateful and do more with less, if we push back individually the headwind is strong. We are negotiating on very uneven terms with employers who know they can ask for more, with less, because everyone does.

So. Have I somehow been encouraged to maintain my “lifestyle” of working at a non-profit cultural heritage institution that is in basic alignment with my values because of the possibility that someday, maybe, the federal government would forgive my student loan debt? The structural forces that shaped my graduate school path and the debt that followed from that are — no offense to the federal government — much larger than the vague possibility of potentially qualifying for a debt forgiveness program could have much impact on. The ship of student loan debt, and the job market we graduated into, had sailed long before the PSLF became a thing that might apply to us a decade in the future.

Ideally — ideally — I would argue that a) the costs of education should be socialized so students aren’t taking on astronomical amounts of personal debt to equip themselves for their jobs and b) the wages paid to entry-level workers in any industry — but perhaps particularly the non-profit / public service worlds — should align with the expenses incurred to train plus the money required to be financially secure. Until that happens, the PSLF program is hardly precipitating the problem of overwhelming student debt. It’s a stop-gap measure to make sure those serving the public for low wages don’t sink beneath the weight of educational debt or evacuate the field entirely because it becomes financially unsustainable. I think it is an entirely appropriate role for government to encourage workers to accept and remain in jobs that service the collective well-being of humanity and to step in and provide a safety net that offsets the financial risk we are currently asked to shoulder.

I have been on income-based repayment for my ~$60k + interest student loan debt since August 2011. I’ve had my employer certified as PSLF-eligible. I’m not holding my breath but I have no other choice because we cannot pay rent and pay standard monthly payments on our debt. This is a systemic problem that requires a systemic solution, and PSLF is one piece of the front line, emergency-response puzzle.

Republicans want 100% of the financial risk of EVERYTHING to be on the individual (student, employee, retiree, sick person, etc. … ). In contrast, I believe — not just because I am one of those touched by the potential of PSLF — that it is a good moral and utilitarian use of government to mitigate the financial burden of education and training in our present reality. If you agree with me, let your representative and senators know! The PSLF is worth fighting for, for all of us, as the first step in reshaping how we fund higher education in the United States. And I’ll be writing my representative Ayanna Pressley, and my senators Elizabeth Warren and Ed Markey, this week to tell them so.

Twitter wants to make EXTRA ‘SPECIALLY SURE that I know it’s

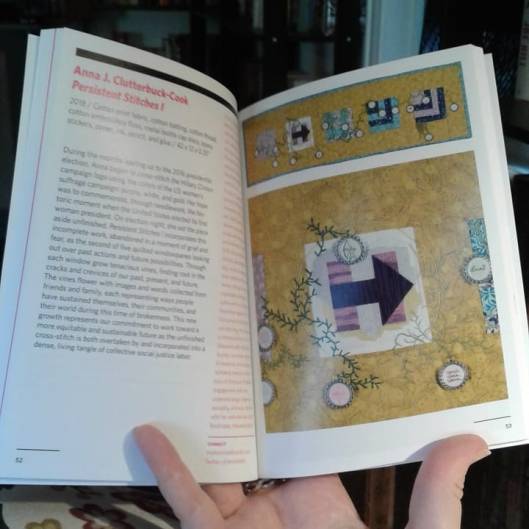

Twitter wants to make EXTRA ‘SPECIALLY SURE that I know it’s  On August 1st the craftivism exhibition

On August 1st the craftivism exhibition

Noble, Safiya Umoja.

Noble, Safiya Umoja.  After reading the book and turning in my review, I had some further thoughts about the way sexually-explicit materials were handled within the text. A thread sharing those thoughts may be found

After reading the book and turning in my review, I had some further thoughts about the way sexually-explicit materials were handled within the text. A thread sharing those thoughts may be found