Over the past few weeks, I’ve read two interesting — if somewhat academic — books about (loosely speaking) print culture and its intersection with queer communities and discourses about non-straight sexuality. The first was Contacts Desired: Gay and Lesbian Communications and Community, 1940s-1970s by Martin Meeker (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006) and the second was Recruiting Young Love: How Christians Talk About Homosexuality by Mark D. Jordan (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011). While the first book dealt largely with homophile organizations and the underground publications of the gay liberation and lesbian feminist movements, the second took up the various rhetorics deployed within Christian circles to speak and write about homosexuality (mostly gay male sexuality) from the turn of the twentieth century through the ex-gay activism of the 1990s. Despite the pro/con nature of these texts, what Contacts Desired and Recruiting Young Love share is an interest in how networks of communication spread ideas and inform opinions, actions, and identities.

“Adolescence is the possibility that desire could be different.”

Recruiting Young Love by Mark D. Jordan, focuses on what he calls “rhetoric” and I might term “discourse” concerning homosexuality — mostly (and he is upfront about this) gay male sexuality — in Christian circles over the course of the twentieth century. His interest is primarily in the 1950s forward, though he does begin in the early twentieth century with the emergence of professional discussion of healthy adolescent development (think G. Stanley Hall, the YMCA, Teddy Roosevelt, etc.) by way of providing background for later debates.

As the phrase “recruiting young love” suggests, Jordan is particularly interested in the way that Christian anti-gay voices expressed anxiety about adolescent sexual identity, and the fact that even today ex-gay therapy understands heterosexual and gender-normative identity to be both the most correct expression of sexuality and the most vulnerable. Teenagers, especially, are seen as vulnerable to recruitment and seduction. The examples of Christian rhetoric concerning homosexuality, then, focus on young people and at times seem to assume that all young men are in fact potentially gay — and that this potentiality is threatening to the moral order.

Although he focuses on anti-gay voices, Jordan also touches on some examples of what he calls “camp spirituality,” or appropriated religious imagery (i.e. the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence), and upon Christian attempts to integrate gay identity and same-sex sexuality into their sexual ethics. He cites, for example, a 1963 Quaker pamphlet, Towards a Quaker View of Sex, that used Alfred Kinsey’s model of fluid sexual practice to argue that homosexual desire and expression, while not predominant, were healthy and normal within the human community. He writes:

For this model of development, most male adolescents are having same-sex relations or thinking about them. Bit by bit, most of them shift over a decade or more to heterosexual relationships. Some do not. The process is not so much an expression of nature as of circumstance or even chance. Indeed, the Quaker pamphlet accepts more fully than any earlier church text not just Kinsey’s terminological suggestion about how to speak of homosexuality as outlet rather than ontology, but his notion that homosexual acts vary with time. To think of yourself as a homosexual should mean no more than observing where you are in the arc of your life and with whom you are now spending it (89).

I was actually quite moved by the idea that one’s sexual “identity” was actually a question of observation and regard, suggesting change over time rather than fixity — though without the sense of enforced change, or charge from “unhealthy” to “healthy” that so many ex-gay narratives imply. Once again, Quakers FTW — and in 1963 no less!

One other aspect of anti-gay Christian rhetoric that Jordan takes note of is the fact that contemporary ex-gay ministries seem to be much more preoccupied with what we would consider gender performance than actual sexual identity, desire, or activity:

Gender matters more than sex [in many ex-gay ministries]. Marriage is the highest accomplishment not because it allows you to copulate naturally, but because it gives you the best stage for performing gender correctly … Indeed, ex-gays may actually be able to use marriage better for gender performance than heterosexuals can, since they are unlikely to enter into it on account of lust … the central category of ‘sexual identity’ means in the end only ‘roles as men and women’ (165).

In this, he relies a great deal on the research and writing of Tanya Erzen, whose recent book Straight to Jesus I reviewed here last August. I’d highly recommend her text if you’re interested in exploring this aspect of the ex-gay movement in more detail.

The weakness of Jordan’s work is one that he admits up-front in the introduction: that it is not meant to be a coherent or comprehensive historical narrative, but rather a series of proffered examples or touch-points meant to give readers a sense of the variety of discourses concerning homosexuality that have existed in Christian circles over the past half century, and some rough idea of where they sprung from, their similarities and their differences. Someone hoping for a more detailed history of anti-gay activism will have to look elsewhere.

“Homosexuals are discarding their furtive ways and openly admitting, even flaunting, their deviation” (Life, 1964).

“Homosexuals are discarding their furtive ways and openly admitting, even flaunting, their deviation” (Life, 1964).Meeker’s Contacts Desired explores the ways by which gay- and lesbian-identified people established networks of communication in the decades before, during, and immediately after what we have come to term “the sexual revolution.” As previous scholars have pointed out, identity based on sexual orientation does not bring with it an automatic community affiliation. Unlike with racial, ethnic, religious, or even class, one rarely grows up in a family that shares one’s non-straight orientation. Particularly during the mid-century in America, where queer subcultures were obscured from public view for the safety of their members, a pervasive sense of isolation was often part and parcel to becoming aware of one’s same-sex desires. Contacts, originally written as Meeker’s PhD dissertation, documents the means by which gay and lesbian individuals made contact with the sexual underground and how they situated themselves within it through text: newsletters, interviews, press releases, pamphlets, “contacts desired” ads, guidebooks, and so forth.

Contacts bears the marks of its academic origins, and I’d suggest picking it up more for targeted rather than leisure reading. Those familiar with the history of mid-twentieth-century gay and lesbian activism will find many of the usual suspects here: the Daughters of Bilitis and the Mattachine Society, lesbian pulps and journalistic (outsider) coverage of gay lives — such as the 1964 Life photographic essay on the gay male subculture, from which the quotation above, and the cover art of Contacts, are drawn.

The primary sources I found most fascinating in Meeker’s work were actually these journalistic offerings from the 1960s, since they offered up a glimpse of (and yes, I know it’s cliche) how far we actually have come in the past fifty years in terms of de-pathologizing and de-criminalizing queer sexualities — even though it’s obvious we still have work to do. Meeker discusses popular book-length treatments of queer subcultures as well as newspaper and magazine exposés. What is clear is that “sympathetic” (straight or passing) writers understood that in order to write about homosexuality for the mainstream, it needed to be treated as a psychological disorder or as antisocial behavior. Understanding homosexuality did not mean reading it as normal. The Life article makes that clear from its sensationalistic opening sentences:

These brawny young men in their leather caps, shirts, jackets and pants are practicing homosexuals, men who turn to other men for affection and sexual satisfaction. They are part of what they call the “gay world,” which is actually a sad and often sordid world. On these pages, LIFE reports on homosexuality in America, on its locale and habits and sums up what science knows and seeks to know about it.

Homosexuality shears across the spectrum of American life – the professional, the arts, business and labor. It always has. But today, especially in big cities, homosexuals are discarding their furtive ways and openly admitting, even flaunting, their deviation. Homosexuals have their own drinking places, their special assignation streets, even their own organizations. And for every obvious homosexual, there are probably nine nearly impossible to detect. This social disorder, which society tries to suppress, has forced itself into the public eye because it dos present a problem – and parents especially are concerned. The myth and misconception with which homosexuality has so long been clothed must be cleared away, not to condone it but to cope with it.

As Meeker points out, these widely-disseminated treatments of homosexuality were often read subversively by those whose desires were the topic of discussion: gay and lesbian readers of Life who might otherwise be cut off from the networks of queer communication and community were given a roadmap to (at least some of) the popular gay and lesbian gathering places or geographic locations, thus offering hope that they were not alone. Articles that claimed to “not … condone [homosexuality] but to cope with it” actually did their part to strengthen the underground networks of queer communication that took a radically different view, at least in most cases, when it came to how sad their lives actually were and the extent to which what sadness there was came as a result of their sexual desires (versus the hostile climate in which they were forced to exist).

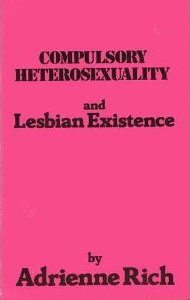

Reading these books has inspired me to explore some of the primary source material itself, so check back next week for reviews of Patricia Highsmith’s The Price of Salt (an early lesbian novel) and Adrienne Rich’s 1977 essay “Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence.”